An alarming trend is developing in ethnic Kachin communities of Burma. Growing poverty, caused by failed state policies, is driving increasing numbers of young people to migrate in search of work. As a result, young women and girls are disappearing without trace, being sold as wives in China, and tricked into the Chinese and Burmese sex industries. Local Kachin researchers conducted interviews in Burma from May-August 2004 in order to document this trend.

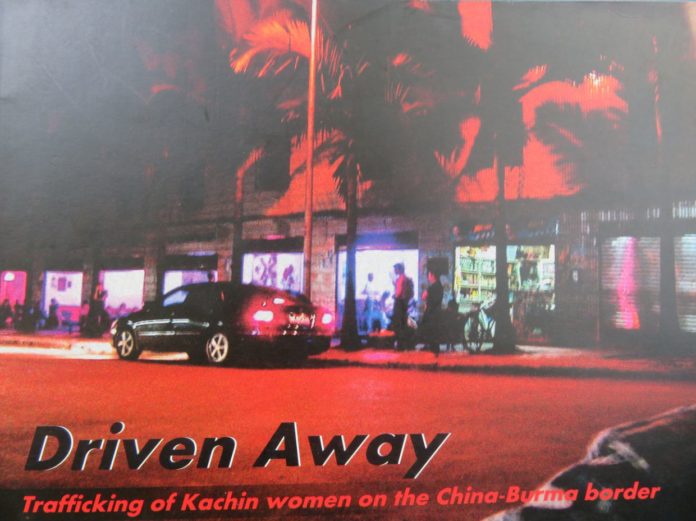

Driven Away: Trafficking of Kachin women on the China-Burma border, produced by the Kachin Women’s Association Thailand (KWAT), is based on 63 verified and suspected trafficking cases that occurred primarily during 2000-2004. The cases involve 85 women and girls, mostly between the ages of 14 and 20. Testimony comes primarily from women and girls who escaped after being trafficked, as well as relatives, persons who helped escapees, and others.

About two-thirds of the women trafficked were from the townships of Myitkyina and Bhamo in Kachin State. About one third were from villages in northern Shan State. In 36 of the cases, women were specifically offered safe work opportunities and followed recruiters to border towns. Many were seeking part-time work to make enough money for school fees during the annual three-month school holiday. Others simply needed to support their families. Those not offered work were taken while looking for work, tricked, or outright abducted.

Women taken to China were most often passed on to traffickers at the border to be transported farther by car, bus and/or train for journeys of up to one week in length. Traffickers used deceit, threats, and drugs to confuse and control women en route.

Women were transported as far as provinces in north-eastern China for the purpose of being sold as wives to Chinese men. Others were trafficked into the sex industry in Chinese border towns or deeper into south-western Yunnan province. Half of the women involved in those cases have disappeared altogether. Only about 10% of the cases involved domestic trafficking, mostly to karaoke bars and massage parlours in the mining areas of Kachin and Shan States.

Most of the cases cited extreme poverty and a lack of employment opportunities in home areas as the main reason for migration. Under the ruling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council or SPDC, Burma’s economy has suffered a devastating deterioration. The regime continues to prioritize military expenditure while its spending on health and education remains negligible. As communities must struggle to provide these services for themselves, by, for example, paying spiralling school costs, families are forced to seek income outside their own communities.

Even after a ceasefire agreement with the Kachin Independence Organisation in 1994, the number of Burma Army troops in Kachin State has tripled, with over 50 Burmese battalions now stationed there. This increased militarization has intensified hardship for local people. Abuses such as land confiscation, forced labour and extortion further impoverish the population.

Against this backdrop of general abuse and impoverishment, Kachin State has been undergoing rapid changes due to large-scale natural resource extraction. Since the ceasefire agreement in 1994, the regime has authorized the exploitation of resources including timber, jade, and gold to be sold mostly as raw products to China. Huge profits have been earned by the Burmese military and Chinese investors, but few benefits have been gained by local communities. There has been no development of resource-based industries to provide long- term sustainable livelihoods. In addition, the “boom town” reality of resource extraction areas encourages the concentration and growth of the sex industry which in turn fuels trafficking.

The regime’s drug eradication policies in northern Shan State have also driven many villagers into poverty. Since 2002, in order to gain international support and funding, the regime has forced farmers in this area to stop growing opium but has not provided them with any alternative means of earning income.

A significant factor that facilitates trafficking is the state’s failure to ensure the provision of identity cards to all citizens in Kachin State. Women and girls without ID cards are denied their right to travel or migrate legally and thus they become vulnerable to trafficking.

While the regime has claimed that it is making efforts to curb trafficking, it is not addressing the root causes that force women to migrate nor the factors that allow trafficking to flourish. Instead, it focuses on anti-trafficking legislation and imposes greater travel restrictions on women. Given that legitimate migration by women is not validated and that corruption has become endemic in military-controlled Burma, travel restrictions and other measures will not only continue to be ineffective, but in fact will facilitate trafficking by forcing women to rely on brokers when they migrate to work.

In just a handful of cases documented for this report were traffickers prosecuted, owing again to corruption and the poverty of the women seeking to press charges. Appeals to the state-sponsored Myanmar Women’s Affairs Federation to assist with prosecution of traffickers have been ineffective.

Women and girls showed a remarkable degree of resourcefulness in managing to escape from situations of trafficking, often thousands of miles from home. Several women were able to return home from eastern China with the aid of Chinese police. However, there does not appear to be a standard procedure for the protection of those trafficked in China. The collusion of local police, lack of language skills and other obstacles to repatriation make safe return very difficult. Upon return, women face penalty by Burmese authorities at the border, and community censure in their hometowns.

There is an urgent need to strengthen community networks that can help raise awareness about issues related to migration and trafficking and to provide services to those that have been trafficked.

It is clear that the problem of trafficking of Kachin women cannot be addressed without challenging the state policies of militarization that are driving communities in Burma into poverty and denying women their basic human rights. Unless there is political reform and restoration of these rights, current inequitable and unsustainable development politices will continue to impoverish local populations, forcing women and girls to migrate to work under conditions that render them vulnerable to trafficking.

Click here to download full report.