Throughout Burma/Myanmar’s history, ethnic nationality communities who have been displaced by conflict have been on the margins of national politics and policy making. They are on the literal peripheries of the country, and are a side-note in the peace and political reform processes. Displaced peoples’ needs are left to the humanitarian efforts of local or international humanitarian organizations. Despite this marginalization, however, displaced people have continued to demonstrate their resiliency, surviving through extreme circumstances and pushing back against attempts to make them return to a situation which is unsafe and ill-prepared to receive them.

International law and standards give displaced people a right to voluntary, safe and dignified return. Any process that seeks to facilitate the return of displaced people to their places of origin or elsewhere must comply with these standards. Above all, direct or indirect measures must not pressure displaced people to return to a situation where their lives and/or freedom would be at risk. Instead, displaced communities must be consulted on all matters that concern them, they must be included in decision making, and their concerns about, and conditions for, return must be taken seriously.

Throughout Burma/Myanmar’s long civil war, ethnic nationality populations in conflict areas have been subjected to a range of human rights abuses, committed primarily by the Burma/Myanmar military. These abuses – forced relocation; military targeting of civilian areas; forced labor; confiscation of crops, property and land; torture; sexual violence and others – and the impact they had on health, education and livelihoods were the primary causes of displacement for almost all people interviewed for this research. Likewise, it is these abuses – not only active conflict – that displaced people fear on return, meaning that ceasefires or a reduction of clashes are not an adequate measure of whether it is safe for displaced people to return home. Furthermore, the abuses they suffered in the past, combined with the lack of accountability, make displaced people fear renewed conflict and serious human rights violations if and when they return.

Conflict and displacement do not affect all people in the same way – women experienced different risks and violations than men, and were even more vulnerable because of their status as ethnic nationality women. Socioeconomic status played a role in when and to where people were displaced, as well as their ability to establish (or not) self-sufficiency after initial displacement. These differences have significant impacts on the challenges displaced populations will face in any return and reintegration.

People who are still displaced face a range of obstacles in meeting their basic needs, with most interviewees relying on outside assistance, from international and/ or local actors, for survival. Restrictions on generating income while living in refugee and formal internally-displaced person (IDP) camps prevent people from seeking sustainable livelihoods. For IDPs outside formal camps, the difficult economic situation of host communities, who are also bearing some of the effects of conflict, makes it difficult for IDPs to find adequate work. Donors and international humanitarian agencies have scaled back support for displaced people, eliminating support for some IDP camps while reducing rations in refugee camps, despite the fact that most of those who remain displaced have no alternative.

Land is a major issue for displaced ethnic communities. Most displaced people interviewed for this research owned land, individually and/or as a community, before they were displaced, and few have been able to regain possession of and title to that land. This is one of the main factors preventing their return. Access to land in sites of displacement is rare, making it difficult to make a living. Land is important not only for livelihoods, but for its sociocultural and community value, including its importance for displaced peoples’ ethnic identity. Restitution of land is one of the most common preconditions displaced people make to consider return. Restitution must be the default remedy, but if restitution is impossible, compensation must be given in the current value of the land and any crops and livestock that were destroyed/confiscated with the land.

Conflict-affected communities across Burma /Myanmar, displaced and non-displaced, face serious livelihood, health and education challenges. Increasing pressures from business and laws that do not protect their interests make them increasingly vulnerable. Community systems of land and natural resource management that have ensured sustainable livelihoods and protection of the natural environment are under threat from neoliberal marketization of land and other aspects of the rural economy. While displaced people face additional challenges due to their displacement, the land and livelihood measures suggested in this report will for the most part only put returnees in a similar situation to that of others in the host communities. It must be stressed that additional, equitable economic, land, agricultural, health and education policies, as well as political reforms to allow increased self-determination, must accompany specific return policies in order to improve the situation of all conflict-affected communities and ensure that returnees’ livelihoods are sustainable. Policies to support returnees must also be accompanied by measures to address the needs of host communities so as not to cause social conflict.

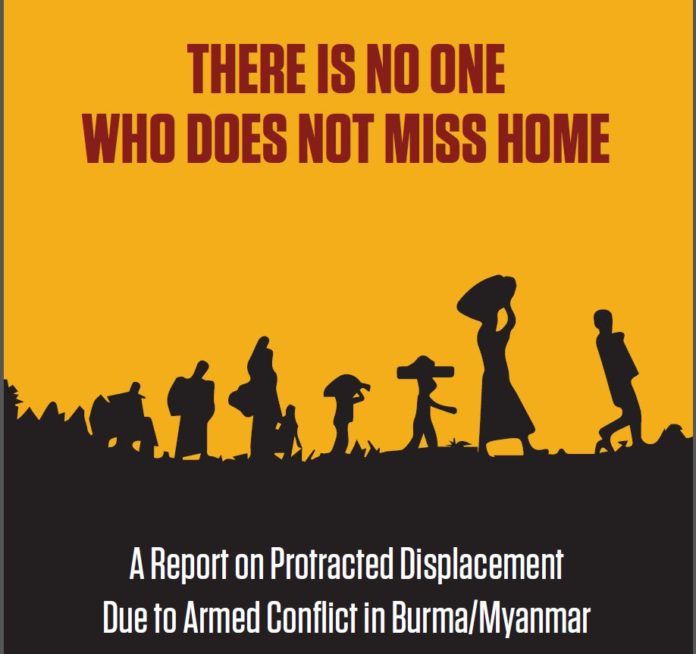

This animation was released on World Refugee Day – 20 June 2019 – to coincide with the launch of a report on protracted displacement due to armed conflict and related human rights violations.

Despite all of their suffering, displaced communities have shown incredible resilience and agency during displacement. They have, to the extent possible, built structures of leadership, mutual support, health and education provision, and environmental protection. A return process that lacks consultation with them and their participation in decision making for their future will not only tear communities apart but risks destroying their resilience and agency. Conversely, a process which supports existing structures of leadership, community and service provision can make return an easier, more empowering and more sustainable process.

Throughout the research process for this report, it became apparent that many within Burma/Myanmar see conflict-affected displaced ethnic populations as lazy, pitiful, and/or somehow rebellious or associated with ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). This appears to impact the treatment of issues related to displacement within the peace process, the general public perception and media coverage of displaced people and their needs, and potentially their reintegration into society. This impression needs to be strongly contested. Displaced people must be treated as Burma/Myanmar citizens equal to all other citizens. They were displaced through no fault of their own, and they are capable of every accomplishment and sentiment of non-displaced in Burma/Myanmar. They have hopes and dreams, they yearn for home and they want to contribute to making their communities and their country a better place. All Burma/Myanmar people should be concerned about the situation of conflict-affected displaced people, and Burma/Myanmar’s leaders should take the lead to respect them and make this issue a national priority. This includes, first and foremost, to develop a holistic and comprehensive plan in consultation with, and participation by, displaced people for their safe, voluntary and dignified return when the conditions are right and if they choose to return. In the meantime, they must be able to live in safety and dignity in their displacement sites.

Click on the link to download full report in [ English ] [ Burmese ].

Source: Progressive Voice Myanmar